Michael Edwards’ specialty is getting perfumers, bottle designers, and fragrance house executives to speak openly about their fragrances—providing in-depth insights for his well-known books that have become an industry standard.

Due to tireless research and thorough investigative reporting, Edwards knows more than most about how many of the world’s most iconic fragrances were conceived.

How was Yves Saint Laurent’s Opium fragrance named? What inspired Chanel No. 5’s perfumer to use aldehydes?

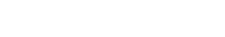

These questions are answered in Edwards’ new book, Perfume Legends II — and Edwards gave fragrance industry insiders the scoop.

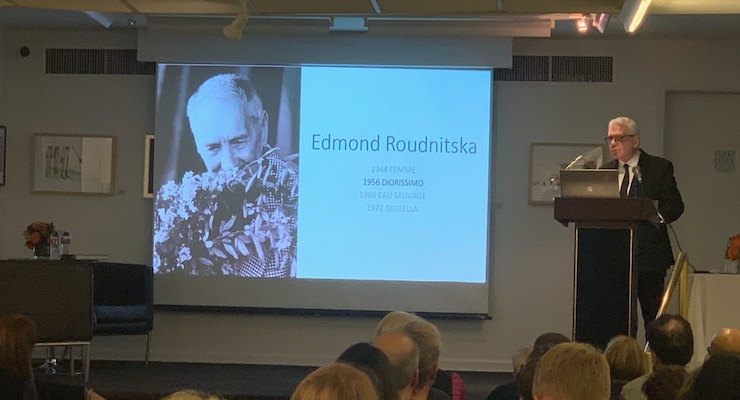

Edwards was the guest of honor at an event organized by the Perfumed Plume Awards for Fragrance Journalism and its founders — Lyn Leigh and Mary Ellen Lapsansky. (Photo in the slideshow above.) Celebrating the American launch of Edwards' new book, Perfumed Plume II, the event was held at the Society of Illustrators in New York last November.

Celebrating 8 New Perfume Legends

Perfume Legends II is a revised and updated version of the original Perfume Legends—with new research, stunning images, and eight new 'legends.'They are: Fracas, Timbuktu, Nahema, Flower by Kenzo, Tocade, Coco Mademoiselle, Portrait of a Lady, J’Adore, and Féminité du Bois.

Edwards told guests captivating stories about how some of the most legendary fragrances and their bottles were created. Next, he sat for a Q&A with Rodrigo Flores-Roux, master perfumer and vice president of perfumery at Givaudan, before he signed his book for guests. (See photo above).

Edwards says that what makes a perfume a legend is— "an accord so innovative that it inspires other compositions, an impact so profound that it shapes a trend—and enduring appeal that transcends fashion."

Opium's Bottle Inspired the Perfume's Name

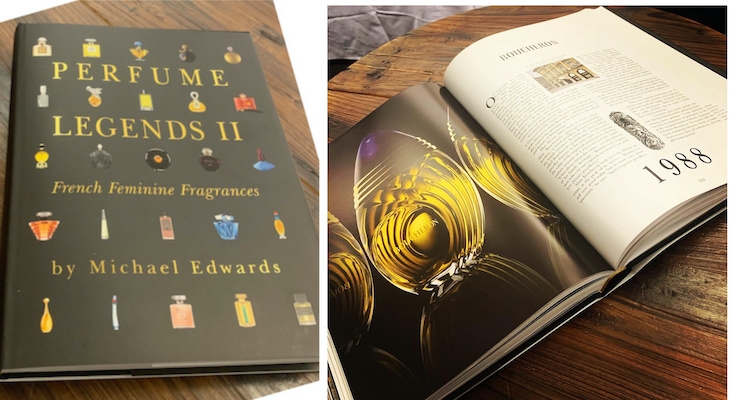

Opium by YSL, which launched in 1977, is one of the ‘legends’ featured in the book. Exactly how much was the French fashion designer, Yves Saint-Laurent, personally involved in the fragrance's development?“It was without a doubt the creation of Yves Saint-Laurent. He said he’d imagined Opium as the perfume the empress of China would order to be created for her,” Edwards says. “Opium was probably the first fragrance to marry emotion to marketing,” he adds.

During his research, Edwards obtained a drawing done by Saint-Laurent. It was how he had first envisioned the Opium bottle — before the fragrance even had a name. “It was almost a Napoleonic kind of bottle with tassels,” says Edwards.

The final bottle was created by Pierre Dinand, of Ateliers Dinand. (See photo above.)

Dinand showed Saint-Laurent his design inspired by a Japanese inro, and Edwards says Dinand recalls the designer saying, “that’s where the samurai would keep their powder, their opium.” And from that drawing, that image, that bottle - came the name of the fragrance.”

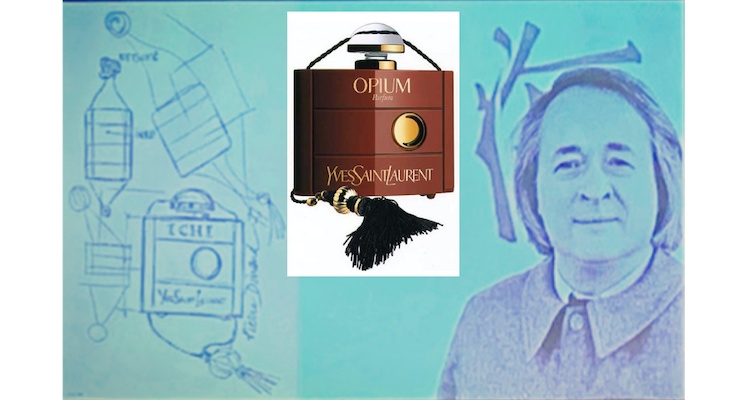

Christian Dior's Lucky Charm—Lily of the Valley

Edwards spoke about Christain Dior, revealing that the designer considered lily of the valley a lucky charm, and always wore a sprig in his buttonhole.“For him, lily of the valley was the ultimate symbol of good luck,” says Edwards. “Whenever it was in bloom, he’d have a little sprig that he’d put on the girls’ hem as they went down the catwalk. If it wasn’t in bloom, he’d have it embroidered on,” he says.

Edmond Roudnitska created Dior’s Diorissimo fragrance in 1956, and many experts say it is the greatest lily of the valley fragrance of all time.

“Of all the Dior fragrances, Diorissimo remained Dior’s favorite,” Edwards says. “Even the packaging is influenced by the house he grew up in — Normandy style, in pink and gray.” (See photos in the slider above, vintage fragrance photo by Etsy/LaParfum)

What Really Inspired the Legendary Chanel No. 5?

Uncovering another moment in fragrance history, Edwards tells the story of Ernest Beaux, the French-Russian chemist and perfumer responsible for the iconic Chanel No. 5, which was created in 1921—and is still a best-seller. (Note: The fragrance’s ‘official’ launch date is 1922.)Edwards discovered that what truly inspired the use of aldehydes in Chanel No. 5 differs from published accounts of how Beaux “played with a modern mix” of various notes to create over 80 versions to present back to ‘Coco’,” as this story reports. Another says the use of aldehydes was a mistake in the lab.

Most accounts say there were ten samples, numbered one to five and 20 to 24 — and Gabrielle ‘Coco’ Chanel chose No. 5.

“These tales make for good marketing stories,” Edwards says, adding, “and there are lovely myths about how he showed her 10 fragrances and then she told him, no, you must change this and you must do that — nothing ever happened like that.”

When asked when he created Chanel No. 5, Edwards found Beaux’s documented reply, which was, “In the spring of 1920, when I came back from Russia.” Beaux was trained as a perfumer in Moscow, and served in French Army during World War I. He was stationed in Murmansk in 1918, which is in northwest Russia, and north of the Arctic Circle.

Edwards says he spent three years tracking down handwritten letters from Beaux, sent from Russia. “It was there that he writes that when spring came along, the rivers bloomed with water plants and the air is filled with a sense of aldehydes,” says Edwards. He read a line from one of Beaux’s letters: “At the time of the midnight sun when the lakes and rivers release a perfume of extreme freshness…”

According to records kept by Beaux and his assistant after the war had ended, Beaux was fascinated with the coriander-like aldehyde scent from Murmansk and worked on replicating it. Development was a challenge, and the first aldehydes Beaux found were unstable. “Eventually he settled on a cocktail of three aldehydes,” Edwards says.

He soon began working on developing Chanel No. 5, with a jasmine note. “He added May rose, ylang-ylang, a little bit of iris — and then of course, the famous aldehydes,” says Edwards. And the rest is fragrance history.