By Anthony L. Almada, MSc, FISSN04.03.20

Over the past 30 years I have delved deeply (via entrepreneurial and clinical research vehicles) into natural bioactives that begin with the letter “C”: creatine, caffeine, carbohydrate. As I write this, I think my next dive may be into yet another “C,” the virology and the virome defined by coronavirus, but that is another story. How did I get to “Cannabis/Cannabinoids/Cannabidiol”?

A few years ago I was speaking with a close friend who is a nutraceutical/dietary supplement executive expatriate and who has become a prominent influencer in the Cannabis world. He was dropping jargon and technical terms that activated my ignorance and inadequacy genes. I was rendered mute, mumbling an unintelligible farewell as the call ended. My reflexive response was to immerse myself in the world’s scientific and patent literature (in three languages). I listened and chimed in on dozens of earnings calls and investor pitch forums. Three months later I came up for air, my mouth agape in disbelief: the gap between the published evidence (in humans) and the evangelical exhortations of investors, sellers, marketers, executives, and even physicians, was as wide as the Mariana Trench is deep.

Here are some of my findings and observations, which have been enriched by attending several cannabinoid-centric scientific conferences, perusing hundreds more original research articles and conference abstracts, and having spirited discussions with academic researchers, colleagues, and manufacturers of cannabidiol-centric ingredients and finished goods (both pharmaceutical and “over the counter”), derived from Cannabis/hemp flower or via chemical or biological synthesis.

What is CBD?

For the scope of this article I will refer to cannabis and its derivatives that possess a concentration of < 0.3% ∆9-tetrahydrocannabinol (∆9-THC, or just THC) as being “hemp.” Cannabidiol (CBD) is a cannabinoid that does not naturally occur in abundance in the flowering parts of hemp. Rather, it exists primarily as a “precursor,” in the acid form (i.e., cannabidiolic acid, or CBDa). This acid form refers to a certain chemical group existing on the CBDa molecule, a carboxylic acid. The application of heat to the harvested flowers is one way in which the acid is liberated from CBDa, releasing CBD. This process is called decarboxylation, or “decarbing.”

One of the most widely used pharmacological attributes assigned to CBD by many researchers and “influencers” is “non-psychoactive” or “non-psychotropic.” This is incorrect, perhaps because of want for a pharmacodynamic descriptor that distinguished the effects of CBD upon mood or affect from that of THC. Caffeine and caffeine-containing beverages, L-theanine, and alcohol, along with many other licit or illicit natural products, can also exert psychoactive/psychotropic effects, yet like CBD, all are non-intoxicating, ethanol being the lone exception.

The practice of calling a hemp derivative that contains “CBD,” not concentrated to near purity (as seen in “CBD isolate”), “CBD,” is equivalent to calling soju (the number one spirit in the world) or vodka, ethanol—for both of these spirits, ethanol comprises 24-40% of the total product. Case in point: a recent series of case reports (no placebo; subjects were fully informed of what they were dosing with) was collected among patients (anxiety, sleep disorders) in an outpatient psychiatry clinic. The title of the paper, and the description of the administered product, used the term “CBD”, yet the commercially available product tested was an extract of hemp wherein the “CBD” is present at a concentration of ≈ 25%.1

The Spawning Grounds of Evidence I: THC as a ‘Trace’ Element

Where did the CBD efficacy-in-humans claims arise from, in relation to sleep or anxiety disorders, or chronic pain and inflammation? No product that one can buy over the counter, or in any dispensary, can claim provenance to any of these studies. The chemistry of most of the drug form CBD used in clinical studies is discrete and precise, unlike all consumer products. Thus, the published clinical evidence base that exists for CBD may not apply to the “CBD”-containing products that are consumer products, especially if they are also comprised of other hemp-derived constituents.

One of the potentially confounding aspects of the earlier published clinical studies conducted with CBD2 is relative impurity (i.e., the presence of THC (in amounts greater than that seen in hemp extracts: ≥ 0.3%). Indeed, in the only approved CBD-centric drug (Epidiolex, for rare seizure disorders), despite the rigorous purification undertaken in its manufacture, THC is present in concentrations that approach 0.15%. This may seem a trivial concentration but because the therapeutic (AKA efficacious) dose of Epidiolex is 10-20 mg of CBD per kg (mg/kg) of body weight, the magnitude of exposure to THC can evolve into physiologically impactful doses (assuming ≈ 0.15% THC concentration).

The daily THC exposures from 10, 15, and 20 mg/kg doses of Epidiolex approximate those of the lowest dose (2.5 mg) found in the first FDA-approved THC drug, Marinol.3 Surprisingly, none of the long-term clinical trials with Epidiolex reported/measured blood THC concentrations in the patients.4-7 Case reports (open label; not randomized and placebo-controlled) have described a sleep-enhancing and nocturnal agitation-reducing effect of nightly doses of 2.5 mg of this synthetic version of THC, among persons with liver disease or dementia, respectively.8-9

The Spawning Grounds of Evidence II: The Voluminous Dose Divide

The Spawning Grounds of Evidence II: The Voluminous Dose Divide

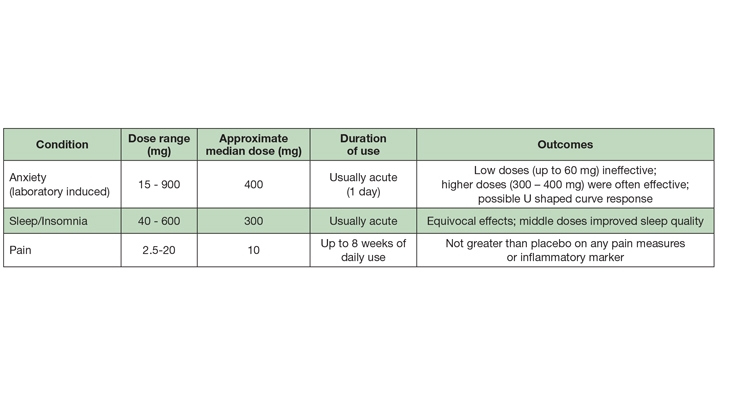

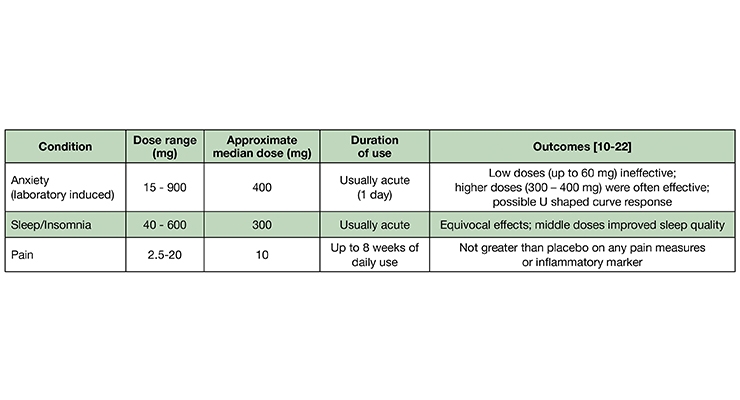

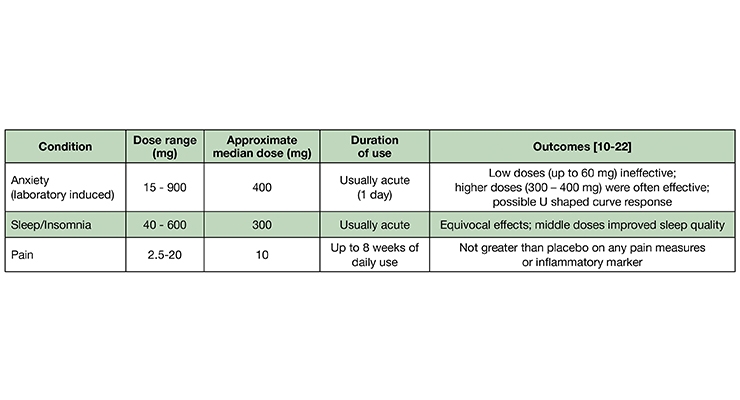

There is a striking incongruity between the recommended doses of “CBD” on consumer goods claiming to contain “CBD” and those used in the published clinical trials. In my surveys and communications with various cannabinoid researchers, “CBD” consumer brand executives, retailers, and hemp post-harvest processors, the median daily dose range recommended (on label) is ≈ 15-50 mg.

Anxiolytic Effects. Two of the earliest studies (1982, 1993) compared the subjective responses to orally administered placebo, CBD, high dose diazepam (10 mg; Valium), THC, and THC + CBD. Although CBD co-administered with THC blunted the intoxicating cannabinoid’s anxiogenic effect, CBD alone (1 mg/kg) did not differ from placebo in inducing self-reported sleepiness among eight healthy men and women;10 CBD (300 mg) did exert anxiolytic effects after a public speaking challenge.11 A study by the same Brazilian group, 35 years later,12 described a dose-dependent “inverted U” response to CBD among persons experiencing public speaking anxiety.11 As self-assessed by post-speech stress questionnaires, the low (100 mg) and high doses (900 mg) did not differ from placebo, while the intermediate dose (300 mg) was superior to placebo and 100 mg CBD, and equivalent to the anxiolytic effects of a benzodiazepine anxiolytic drug (clonazepam; Klonopin), as self-assessed with a post-speech mood scale. There do not appear to be any chronic controlled trials (≥ 1 week) evaluating the anxiolytic effects of CBD in persons with Generalized Anxiety Disorder.13

Sleep Modulation. One of the first controlled clinical studies (1980) conducted with pure CBD assessed its safety and tolerability in 16 healthy, young Brazilian men and women (over 30 days), at doses of 3-6 mg/kg, divided into two doses, daily.2 Two of the eight subjects randomized to receive CBD reported a somnolent effect, one during the first week and the other throughout the duration of the study. An additional subject, with a history of mild insomnia, reported being able to sleep better during the first week of medication but not thereafter.

Additional studies by the same researchers performed in the 1970s and reported in 1981 compared the effects of three doses (40, 80, and 160 mg) of pure CBD to placebo and a benzodiazepine drug (nitrazepam; a chemical cousin of diazepam [Valium]) among 15 otherwise healthy subjects with a history of insomnia.15 Each subject took each treatment, once weekly (30 minutes before bedtime), with a one-week washout between treatments [Note: the doses were provided only once weekly because of the limited supply of CBD afforded to the research group]. The placebo effect obscured any improvement in sleep onset. However, the highest dose (160 mg) of CBD was self-reported to lengthen sleep duration and improve sleep quality among two-thirds of the subjects. The two lower doses were equivalent to placebo. Notably, dream recall was reduced by all three CBD doses.

The most rigorously-controlled sleep study also included polysomnographic equipment to objectively measure sleep and neurophysiology (total sleep time, sleep onset latency, all four sleep stages, etc.).16 In this crossover study, 26 young, healthy women and men were randomly assigned to acutely receive 300 mg of near pure CBD (drug grade; a form used in several controlled clinical trials with CBD, with undetectable THC—one of the very few studies to explicitly assert this) or placebo. Among all of the measures performed, including cognitive and subjective scoring, CBD did not differ from placebo. Clearly, chronic dosing studies among persons living with disordered sleep are warranted.

Analgesic/Anti-Inflammatory. “CBD” for pain? The nearly ubiquitous attribution of “analgesic” to CBD remains enigmatic, given the complete lack of controlled studies demonstrating such. This “habit” of assigning analgesic status, without explicitly excluding co-administration with THC, appears to infect cannabinoid researchers of repute: a group of Brazilian researchers that has conducted dozens of clinical trials with CBD-centric compositions (a group that is cited in this article four times), begins a recent publication with the statement: “Cannabidiol (CBD), one of the major compounds of Cannabis sativa, has been shown to have several therapeutic effects including… analgesic properties [reference]…”.17 Perusal of this reference (a review paper co-authored by a clinical dentist and four dentists/academic researchers) yields the disappointing finding that all of the studies referred to used THC + CBD or THC alone (in various forms). No studies used CBD unattended by THC.

A very prominent cannabinoid pharmaceutical company in Canada, listed on the NASDAQ (and which has endured a 94% drop in market cap, at the time of this writing), sent out an e-mail blast, including a statement claiming “CBD can be used for pain.” I sent a request for studies in humans supporting such a statement. When the “evidence-based” response was delivered I laughed aloud: a study where rats with chemically induced osteoarthritis were then injected—into the inflamed, painful joint—with research-grade CBD (which contains uncharacterized impurities; they did not use drug-form CBD).18

In what may be the only orally administered randomized controlled trial, 19 men and women with Crohn’s disease (average duration of ≈ 12 years) were randomized to receive placebo (olive oil) or CBD (99.5% pure, 10 mg) in olive oil (in a dropper bottle), to be taken twice daily, for eight weeks.19 The CBD intervention equaled the placebo in self-scoring of symptoms, and in blood concentrations of an inflammation marker (C-reactive protein).

A study from late last year compared four different THC:CBD compositions, administered via a thoroughly investigated vaping device, among patients with chronic pain associated with fibromyalgia.20 The results from a single inhalation of the high CBD/low THC product were “…devoid of analgesic activity in any of the spontaneous or evoked pain models.”

A study employing an “N of 1” design—where the patients are studied as individuals (rather than as a group)—were subjected to rigorous double blind, placebo controlled conditions, with a crossover to other treatments or placebo.21 In this 2004 study from England, sublingual sprays (made by GW Pharmaceuticals, the manufacturer of Epidiolex) with differing CBD and THC contents (or placebo) were compared in patients presenting with a diverse variety of chronic pain types, each treatment being used for one week. The patients preferred the THC-containing sprays; for the CBD (>95% CBD) spray the authors concluded: “The lack of effect of CBD by itself may just reflect either the narrow range of pain problems studied and/or the need for a substantially higher dose of CBD.” [The daily dose ranged from 2.5 – 15 mg.]

A similar design study from England, enrolling mostly patients with multiple sclerosis, also found the CBD sublingual spray to be no better than placebo for pain.22

The Entourage Enchantment

I have faith in the potential of a synergistic interaction among constituents in a plant extract, including hemp (which means < 0.3% THC), but I have yet to find evidence to support this. Evangelists of the “entourage effect,” which has morphed from its original meaning from over 20 years ago (an active compound presented along with its “inactive” companion molecules, in a plant or animal23)to now mean that a polymolecular hemp/cannabis extract or concentrate is more bioactive/efficacious than an isolated constituent (e.g., “broad spectrum” hemp flower extract vs. “CBD isolate.”

A few companies, including a prominent practitioner brand with international distribution, have introduced CBD-centric hemp extracts and cite research publications affirming the entourage effect (this presumably renders their product superior to an isolate of CBD). However, a read of the animal studies invoked reveals a fatal flaw: they use CBD-rich extracts that exceed the <0.3% THC concentration threshold by 4-10 times.24-25 I am befuddled as to how these ultra-germane aspects are overlooked (or unrecognized).

It CAN’T Be ALL Placebo!?

A minority of critics (whom are true experts in a variety of life sciences areas, including cannabinoids) have been saying that no evidence supports the safety and efficacy (in humans) of products available in commerce. Indeed, the gap between the evidence and evangelical claims tsunami is vast. How will this be bridged, what is the prediction of the landscape in 1-2 years, and where are the open holes? First, very few studies that measure outcomes (e.g., sleep modulation) also measure blood concentrations of CBD and its metabolome. CBD is terribly absorbed—it is MALabsorbed. I have advocated to all of my friends and colleagues that ask for advice, to always take it with a fat-rich meal. The “food effect” of CBD (as for many other water-insoluble drugs) may be dramatic.26 With CBD being so poorly absorbed, the advocated doses being sub-pharmacological—at least in relation to the evidence base—and the cost of evidence-based dosing being economically untenable for many, other factors may mediate the biological responses observed/enjoyed by many. They may be indirect, and/or may be mediated by other constituents in the plant. What is urgently needed is a head to head comparison study between a pure, drug form of CBD and a hemp extract that bears the same amount of CBD and the remaining fraction of other bioactives (far from full spectrum, as there are several hundred constituents and only a relative few are measured). I cannot predict what will happen but the indicators suggest that “CBD” (as consumer products) will not enjoy robust efficacy status. Let’s hope it scores high on safety. Come back and ask me two to three years from now, “How big is the gap, now?”

Anthony L. Almada is trained as a nutritional & exercise biochemist, has worked in the natural products industry since 1975, and been a co-investigator on over 50 univeristy-based clinical trials. His first encounter with therapeutic cannabinoids was while collaborating on a university-based clinical trial in AIDS patients in 1996.

References

1. Shannon S, et al. Cannabidiol in anxiety and sleep: A large case series. Perm J 2019;23:18-041. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7812/TPP/18-041

2. Chronic administration of cannabidiol to healthy volunteers and epileptic patients. Pharmacology 1980;21:175-85.

3. https://www.rxabbvie.com/pdf/marinol_PI.pdf

4. Szaflarski JP, et al. Long‐term safety and treatment effects of cannabidiol in children and adults with treatment‐resistant epilepsies: Expanded access program results. Epilepsia 2018;59:1540-8.

5. Devinsky O, et al. Effect of cannabidiol on drop seizures in the Lennox–Gastaut syndrome. N Engl J Med 2018;378:1888-97.

6. Devinsky O, et al. Trial of cannabidiol for drug-resistant seizures in the Dravet

syndrome. N Engl J Med 2017;376:2011-20.

7. Thiele EA, et al. Cannabidiol in patients with seizures associated with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (GWPCARE4): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. The Lancet. 2018;391: 1085–96.

8. Neff GW, et al. Preliminary observation with dronabinol in patients with intractable pruritus secondary to cholestatic liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2002;97:2117-9.

9. Walther S, et al. Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol for nighttime agitation in severe dementia. Psychopharmacology 2006;185:524–8.

10. Zuardi AW, et al. Action of cannabidiol on the anxiety and other effects produced by a ∆9-THC in normal subjects. Psychopharmacology 1982;76:245-50.

11. Zuardi AW, et al. Effects of ipsapirone and cannabidiol on human experimental anxiety. J Psychopharmacology 1993;7:82-8.

12. Zuardi AW, et al. Inverted U-shaped dose-response curve of the anxiolytic effect of cannabidiol during public speaking in real life. Front Pharmacol 2017;8:259.

13. Blessing EM, et al. Cannabidiol as a potential treatment for anxiety disorders.

Neurotherapeutics 2015;12:825–36.

14. Lee JLC, et al. Cannabidiol regulation of emotion and emotional memory processing: relevance for treating anxiety-related and substance abuse disorders. Br J Pharmacol 2017;174:3242–56.

15. Carlini EA, Cunha JM. Hypnotic and antiepileptic effects of cannabidiol. J Clin Pharmacol 1981;21:417S-27S.

16. Linares IMP, et al. No acute effects of cannabidiol on the sleep-wake cycle of healthy subjects: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study. Front Pharmacol 2018;9:315.

17. Boychuk DG, et al. The effectiveness of cannabinoids in the management of chronic, nonmalignant neuropathic pain: A systematic review. J Oral Facial Pain Headache 2015;29:7-14.

18. Philpott HT, et al. Attenuation of early phase inflammation by cannabidiol prevents pain and nerve damage in rat osteoarthritis. Pain 2017;158:2442–51.

19. Naftali T, et al. Low dose cannabidiol is safe but not effective in the treatment

for Crohn’s disease, a randomized controlled trial. Dig Dis Sci 2017;62:1615–20.

20. van de Donk T, et al. An experimental randomized study on the analgesic effects of pharmaceutical-grade Cannabis in chronic pain patients with fibromyalgia. Pain 2019;160:860–9.

21. Notcutt, W, et al. Initial experiences with medicinal extracts of cannabis for chronic pain: Results from 34 ‘N of 1’ studies.Anaesthesia 2004;59:440–52.

22. Wade DT, et al. A preliminary controlled study to determine whether whole-plant cannabis extracts can improve intractable neurogenic symptoms Clin Rehab 2003;17:21–9.

23. Ben-Shabat S, et al. An entourage effect: inactive endogenous fatty acid glycerol esters enhance 2-arachidonoyl-glycerol cannabinoid activity. Eur J Pharmacol 1998;353:23–31.

24. Gallily R, et al. Overcoming the bell-shaped dose-response of cannabidiol by using Cannabis extract enriched in cannabidiol. Pharmacol Pharm 2015;6:75‐85.

25. Pagano E, et al. An orally active cannabis extract with high content in cannabidiol attenuates chemically-induced intestinal inflammation and hypermotility in the mouse. Front Pharmacol 2016;7:341.

26. Taylor L, et al. A phase I, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, single ascending dose, multiple dose, and food effect trial of the safety, tolerability and pharmacokinetics of highly purified cannabidiol in healthy subjects. CNS Drugs 2018;32:1053-67.

A few years ago I was speaking with a close friend who is a nutraceutical/dietary supplement executive expatriate and who has become a prominent influencer in the Cannabis world. He was dropping jargon and technical terms that activated my ignorance and inadequacy genes. I was rendered mute, mumbling an unintelligible farewell as the call ended. My reflexive response was to immerse myself in the world’s scientific and patent literature (in three languages). I listened and chimed in on dozens of earnings calls and investor pitch forums. Three months later I came up for air, my mouth agape in disbelief: the gap between the published evidence (in humans) and the evangelical exhortations of investors, sellers, marketers, executives, and even physicians, was as wide as the Mariana Trench is deep.

Here are some of my findings and observations, which have been enriched by attending several cannabinoid-centric scientific conferences, perusing hundreds more original research articles and conference abstracts, and having spirited discussions with academic researchers, colleagues, and manufacturers of cannabidiol-centric ingredients and finished goods (both pharmaceutical and “over the counter”), derived from Cannabis/hemp flower or via chemical or biological synthesis.

What is CBD?

For the scope of this article I will refer to cannabis and its derivatives that possess a concentration of < 0.3% ∆9-tetrahydrocannabinol (∆9-THC, or just THC) as being “hemp.” Cannabidiol (CBD) is a cannabinoid that does not naturally occur in abundance in the flowering parts of hemp. Rather, it exists primarily as a “precursor,” in the acid form (i.e., cannabidiolic acid, or CBDa). This acid form refers to a certain chemical group existing on the CBDa molecule, a carboxylic acid. The application of heat to the harvested flowers is one way in which the acid is liberated from CBDa, releasing CBD. This process is called decarboxylation, or “decarbing.”

One of the most widely used pharmacological attributes assigned to CBD by many researchers and “influencers” is “non-psychoactive” or “non-psychotropic.” This is incorrect, perhaps because of want for a pharmacodynamic descriptor that distinguished the effects of CBD upon mood or affect from that of THC. Caffeine and caffeine-containing beverages, L-theanine, and alcohol, along with many other licit or illicit natural products, can also exert psychoactive/psychotropic effects, yet like CBD, all are non-intoxicating, ethanol being the lone exception.

The practice of calling a hemp derivative that contains “CBD,” not concentrated to near purity (as seen in “CBD isolate”), “CBD,” is equivalent to calling soju (the number one spirit in the world) or vodka, ethanol—for both of these spirits, ethanol comprises 24-40% of the total product. Case in point: a recent series of case reports (no placebo; subjects were fully informed of what they were dosing with) was collected among patients (anxiety, sleep disorders) in an outpatient psychiatry clinic. The title of the paper, and the description of the administered product, used the term “CBD”, yet the commercially available product tested was an extract of hemp wherein the “CBD” is present at a concentration of ≈ 25%.1

The Spawning Grounds of Evidence I: THC as a ‘Trace’ Element

Where did the CBD efficacy-in-humans claims arise from, in relation to sleep or anxiety disorders, or chronic pain and inflammation? No product that one can buy over the counter, or in any dispensary, can claim provenance to any of these studies. The chemistry of most of the drug form CBD used in clinical studies is discrete and precise, unlike all consumer products. Thus, the published clinical evidence base that exists for CBD may not apply to the “CBD”-containing products that are consumer products, especially if they are also comprised of other hemp-derived constituents.

One of the potentially confounding aspects of the earlier published clinical studies conducted with CBD2 is relative impurity (i.e., the presence of THC (in amounts greater than that seen in hemp extracts: ≥ 0.3%). Indeed, in the only approved CBD-centric drug (Epidiolex, for rare seizure disorders), despite the rigorous purification undertaken in its manufacture, THC is present in concentrations that approach 0.15%. This may seem a trivial concentration but because the therapeutic (AKA efficacious) dose of Epidiolex is 10-20 mg of CBD per kg (mg/kg) of body weight, the magnitude of exposure to THC can evolve into physiologically impactful doses (assuming ≈ 0.15% THC concentration).

The daily THC exposures from 10, 15, and 20 mg/kg doses of Epidiolex approximate those of the lowest dose (2.5 mg) found in the first FDA-approved THC drug, Marinol.3 Surprisingly, none of the long-term clinical trials with Epidiolex reported/measured blood THC concentrations in the patients.4-7 Case reports (open label; not randomized and placebo-controlled) have described a sleep-enhancing and nocturnal agitation-reducing effect of nightly doses of 2.5 mg of this synthetic version of THC, among persons with liver disease or dementia, respectively.8-9

There is a striking incongruity between the recommended doses of “CBD” on consumer goods claiming to contain “CBD” and those used in the published clinical trials. In my surveys and communications with various cannabinoid researchers, “CBD” consumer brand executives, retailers, and hemp post-harvest processors, the median daily dose range recommended (on label) is ≈ 15-50 mg.

Anxiolytic Effects. Two of the earliest studies (1982, 1993) compared the subjective responses to orally administered placebo, CBD, high dose diazepam (10 mg; Valium), THC, and THC + CBD. Although CBD co-administered with THC blunted the intoxicating cannabinoid’s anxiogenic effect, CBD alone (1 mg/kg) did not differ from placebo in inducing self-reported sleepiness among eight healthy men and women;10 CBD (300 mg) did exert anxiolytic effects after a public speaking challenge.11 A study by the same Brazilian group, 35 years later,12 described a dose-dependent “inverted U” response to CBD among persons experiencing public speaking anxiety.11 As self-assessed by post-speech stress questionnaires, the low (100 mg) and high doses (900 mg) did not differ from placebo, while the intermediate dose (300 mg) was superior to placebo and 100 mg CBD, and equivalent to the anxiolytic effects of a benzodiazepine anxiolytic drug (clonazepam; Klonopin), as self-assessed with a post-speech mood scale. There do not appear to be any chronic controlled trials (≥ 1 week) evaluating the anxiolytic effects of CBD in persons with Generalized Anxiety Disorder.13

Sleep Modulation. One of the first controlled clinical studies (1980) conducted with pure CBD assessed its safety and tolerability in 16 healthy, young Brazilian men and women (over 30 days), at doses of 3-6 mg/kg, divided into two doses, daily.2 Two of the eight subjects randomized to receive CBD reported a somnolent effect, one during the first week and the other throughout the duration of the study. An additional subject, with a history of mild insomnia, reported being able to sleep better during the first week of medication but not thereafter.

Additional studies by the same researchers performed in the 1970s and reported in 1981 compared the effects of three doses (40, 80, and 160 mg) of pure CBD to placebo and a benzodiazepine drug (nitrazepam; a chemical cousin of diazepam [Valium]) among 15 otherwise healthy subjects with a history of insomnia.15 Each subject took each treatment, once weekly (30 minutes before bedtime), with a one-week washout between treatments [Note: the doses were provided only once weekly because of the limited supply of CBD afforded to the research group]. The placebo effect obscured any improvement in sleep onset. However, the highest dose (160 mg) of CBD was self-reported to lengthen sleep duration and improve sleep quality among two-thirds of the subjects. The two lower doses were equivalent to placebo. Notably, dream recall was reduced by all three CBD doses.

The most rigorously-controlled sleep study also included polysomnographic equipment to objectively measure sleep and neurophysiology (total sleep time, sleep onset latency, all four sleep stages, etc.).16 In this crossover study, 26 young, healthy women and men were randomly assigned to acutely receive 300 mg of near pure CBD (drug grade; a form used in several controlled clinical trials with CBD, with undetectable THC—one of the very few studies to explicitly assert this) or placebo. Among all of the measures performed, including cognitive and subjective scoring, CBD did not differ from placebo. Clearly, chronic dosing studies among persons living with disordered sleep are warranted.

Analgesic/Anti-Inflammatory. “CBD” for pain? The nearly ubiquitous attribution of “analgesic” to CBD remains enigmatic, given the complete lack of controlled studies demonstrating such. This “habit” of assigning analgesic status, without explicitly excluding co-administration with THC, appears to infect cannabinoid researchers of repute: a group of Brazilian researchers that has conducted dozens of clinical trials with CBD-centric compositions (a group that is cited in this article four times), begins a recent publication with the statement: “Cannabidiol (CBD), one of the major compounds of Cannabis sativa, has been shown to have several therapeutic effects including… analgesic properties [reference]…”.17 Perusal of this reference (a review paper co-authored by a clinical dentist and four dentists/academic researchers) yields the disappointing finding that all of the studies referred to used THC + CBD or THC alone (in various forms). No studies used CBD unattended by THC.

A very prominent cannabinoid pharmaceutical company in Canada, listed on the NASDAQ (and which has endured a 94% drop in market cap, at the time of this writing), sent out an e-mail blast, including a statement claiming “CBD can be used for pain.” I sent a request for studies in humans supporting such a statement. When the “evidence-based” response was delivered I laughed aloud: a study where rats with chemically induced osteoarthritis were then injected—into the inflamed, painful joint—with research-grade CBD (which contains uncharacterized impurities; they did not use drug-form CBD).18

In what may be the only orally administered randomized controlled trial, 19 men and women with Crohn’s disease (average duration of ≈ 12 years) were randomized to receive placebo (olive oil) or CBD (99.5% pure, 10 mg) in olive oil (in a dropper bottle), to be taken twice daily, for eight weeks.19 The CBD intervention equaled the placebo in self-scoring of symptoms, and in blood concentrations of an inflammation marker (C-reactive protein).

A study from late last year compared four different THC:CBD compositions, administered via a thoroughly investigated vaping device, among patients with chronic pain associated with fibromyalgia.20 The results from a single inhalation of the high CBD/low THC product were “…devoid of analgesic activity in any of the spontaneous or evoked pain models.”

A study employing an “N of 1” design—where the patients are studied as individuals (rather than as a group)—were subjected to rigorous double blind, placebo controlled conditions, with a crossover to other treatments or placebo.21 In this 2004 study from England, sublingual sprays (made by GW Pharmaceuticals, the manufacturer of Epidiolex) with differing CBD and THC contents (or placebo) were compared in patients presenting with a diverse variety of chronic pain types, each treatment being used for one week. The patients preferred the THC-containing sprays; for the CBD (>95% CBD) spray the authors concluded: “The lack of effect of CBD by itself may just reflect either the narrow range of pain problems studied and/or the need for a substantially higher dose of CBD.” [The daily dose ranged from 2.5 – 15 mg.]

A similar design study from England, enrolling mostly patients with multiple sclerosis, also found the CBD sublingual spray to be no better than placebo for pain.22

The Entourage Enchantment

I have faith in the potential of a synergistic interaction among constituents in a plant extract, including hemp (which means < 0.3% THC), but I have yet to find evidence to support this. Evangelists of the “entourage effect,” which has morphed from its original meaning from over 20 years ago (an active compound presented along with its “inactive” companion molecules, in a plant or animal23)to now mean that a polymolecular hemp/cannabis extract or concentrate is more bioactive/efficacious than an isolated constituent (e.g., “broad spectrum” hemp flower extract vs. “CBD isolate.”

A few companies, including a prominent practitioner brand with international distribution, have introduced CBD-centric hemp extracts and cite research publications affirming the entourage effect (this presumably renders their product superior to an isolate of CBD). However, a read of the animal studies invoked reveals a fatal flaw: they use CBD-rich extracts that exceed the <0.3% THC concentration threshold by 4-10 times.24-25 I am befuddled as to how these ultra-germane aspects are overlooked (or unrecognized).

It CAN’T Be ALL Placebo!?

A minority of critics (whom are true experts in a variety of life sciences areas, including cannabinoids) have been saying that no evidence supports the safety and efficacy (in humans) of products available in commerce. Indeed, the gap between the evidence and evangelical claims tsunami is vast. How will this be bridged, what is the prediction of the landscape in 1-2 years, and where are the open holes? First, very few studies that measure outcomes (e.g., sleep modulation) also measure blood concentrations of CBD and its metabolome. CBD is terribly absorbed—it is MALabsorbed. I have advocated to all of my friends and colleagues that ask for advice, to always take it with a fat-rich meal. The “food effect” of CBD (as for many other water-insoluble drugs) may be dramatic.26 With CBD being so poorly absorbed, the advocated doses being sub-pharmacological—at least in relation to the evidence base—and the cost of evidence-based dosing being economically untenable for many, other factors may mediate the biological responses observed/enjoyed by many. They may be indirect, and/or may be mediated by other constituents in the plant. What is urgently needed is a head to head comparison study between a pure, drug form of CBD and a hemp extract that bears the same amount of CBD and the remaining fraction of other bioactives (far from full spectrum, as there are several hundred constituents and only a relative few are measured). I cannot predict what will happen but the indicators suggest that “CBD” (as consumer products) will not enjoy robust efficacy status. Let’s hope it scores high on safety. Come back and ask me two to three years from now, “How big is the gap, now?”

Anthony L. Almada is trained as a nutritional & exercise biochemist, has worked in the natural products industry since 1975, and been a co-investigator on over 50 univeristy-based clinical trials. His first encounter with therapeutic cannabinoids was while collaborating on a university-based clinical trial in AIDS patients in 1996.

References

1. Shannon S, et al. Cannabidiol in anxiety and sleep: A large case series. Perm J 2019;23:18-041. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7812/TPP/18-041

2. Chronic administration of cannabidiol to healthy volunteers and epileptic patients. Pharmacology 1980;21:175-85.

3. https://www.rxabbvie.com/pdf/marinol_PI.pdf

4. Szaflarski JP, et al. Long‐term safety and treatment effects of cannabidiol in children and adults with treatment‐resistant epilepsies: Expanded access program results. Epilepsia 2018;59:1540-8.

5. Devinsky O, et al. Effect of cannabidiol on drop seizures in the Lennox–Gastaut syndrome. N Engl J Med 2018;378:1888-97.

6. Devinsky O, et al. Trial of cannabidiol for drug-resistant seizures in the Dravet

syndrome. N Engl J Med 2017;376:2011-20.

7. Thiele EA, et al. Cannabidiol in patients with seizures associated with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (GWPCARE4): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. The Lancet. 2018;391: 1085–96.

8. Neff GW, et al. Preliminary observation with dronabinol in patients with intractable pruritus secondary to cholestatic liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2002;97:2117-9.

9. Walther S, et al. Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol for nighttime agitation in severe dementia. Psychopharmacology 2006;185:524–8.

10. Zuardi AW, et al. Action of cannabidiol on the anxiety and other effects produced by a ∆9-THC in normal subjects. Psychopharmacology 1982;76:245-50.

11. Zuardi AW, et al. Effects of ipsapirone and cannabidiol on human experimental anxiety. J Psychopharmacology 1993;7:82-8.

12. Zuardi AW, et al. Inverted U-shaped dose-response curve of the anxiolytic effect of cannabidiol during public speaking in real life. Front Pharmacol 2017;8:259.

13. Blessing EM, et al. Cannabidiol as a potential treatment for anxiety disorders.

Neurotherapeutics 2015;12:825–36.

14. Lee JLC, et al. Cannabidiol regulation of emotion and emotional memory processing: relevance for treating anxiety-related and substance abuse disorders. Br J Pharmacol 2017;174:3242–56.

15. Carlini EA, Cunha JM. Hypnotic and antiepileptic effects of cannabidiol. J Clin Pharmacol 1981;21:417S-27S.

16. Linares IMP, et al. No acute effects of cannabidiol on the sleep-wake cycle of healthy subjects: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study. Front Pharmacol 2018;9:315.

17. Boychuk DG, et al. The effectiveness of cannabinoids in the management of chronic, nonmalignant neuropathic pain: A systematic review. J Oral Facial Pain Headache 2015;29:7-14.

18. Philpott HT, et al. Attenuation of early phase inflammation by cannabidiol prevents pain and nerve damage in rat osteoarthritis. Pain 2017;158:2442–51.

19. Naftali T, et al. Low dose cannabidiol is safe but not effective in the treatment

for Crohn’s disease, a randomized controlled trial. Dig Dis Sci 2017;62:1615–20.

20. van de Donk T, et al. An experimental randomized study on the analgesic effects of pharmaceutical-grade Cannabis in chronic pain patients with fibromyalgia. Pain 2019;160:860–9.

21. Notcutt, W, et al. Initial experiences with medicinal extracts of cannabis for chronic pain: Results from 34 ‘N of 1’ studies.Anaesthesia 2004;59:440–52.

22. Wade DT, et al. A preliminary controlled study to determine whether whole-plant cannabis extracts can improve intractable neurogenic symptoms Clin Rehab 2003;17:21–9.

23. Ben-Shabat S, et al. An entourage effect: inactive endogenous fatty acid glycerol esters enhance 2-arachidonoyl-glycerol cannabinoid activity. Eur J Pharmacol 1998;353:23–31.

24. Gallily R, et al. Overcoming the bell-shaped dose-response of cannabidiol by using Cannabis extract enriched in cannabidiol. Pharmacol Pharm 2015;6:75‐85.

25. Pagano E, et al. An orally active cannabis extract with high content in cannabidiol attenuates chemically-induced intestinal inflammation and hypermotility in the mouse. Front Pharmacol 2016;7:341.

26. Taylor L, et al. A phase I, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, single ascending dose, multiple dose, and food effect trial of the safety, tolerability and pharmacokinetics of highly purified cannabidiol in healthy subjects. CNS Drugs 2018;32:1053-67.